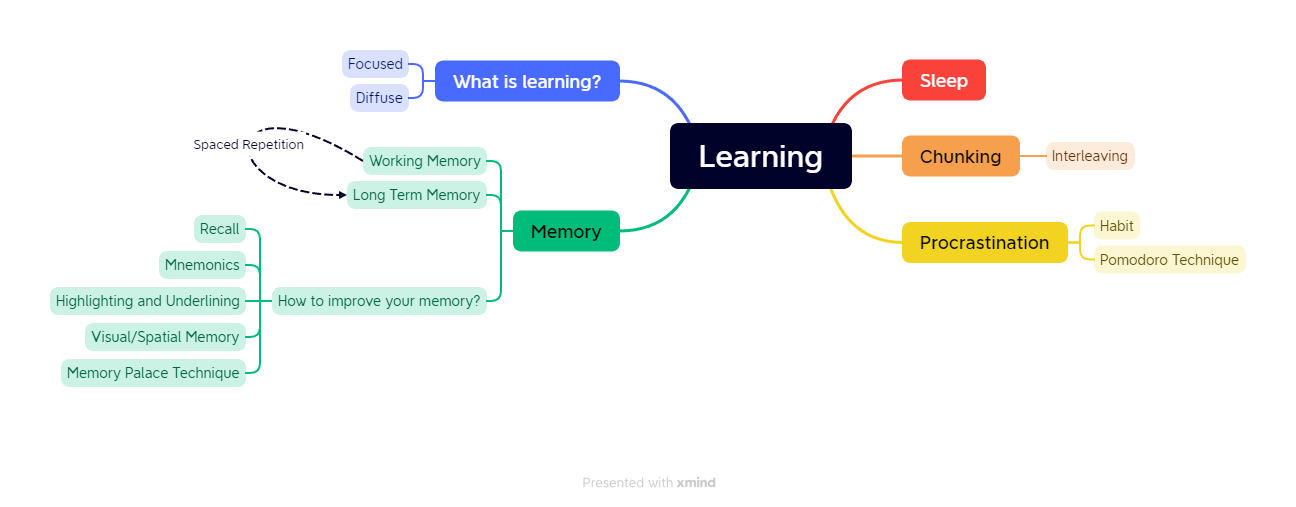

Learning How to Learn

Notes from the Learning How to Learn Book By Barbara Oakley.

Contents

Summary

In a world that’s constantly evolving, the ability to learn efficiently and effectively is a skill that can unlock doors to personal and professional growth. Whether you’re a student striving for academic excellence, a professional seeking to stay competitive in your career, or simply someone who wants to enhance their ability to acquire new knowledge, the Learn How to Learn book is a valuable resource that can empower you to do just that.

This book has garnered attention from learners of all backgrounds. It delves into the science behind learning and equips you with proven strategies to enhance your learning abilities. As we explore the key takeaways from this book, you’ll discover how to overcome common obstacles, develop effective study habits, and harness the power of your brain to grasp new concepts with confidence.

Main Takeaways

1/ What is learning?

There are two different modes of thinking:

- Focused: concentrate intently on something you’re trying to learn or to understand

- Diffuse: relaxed thinking style related to a set of neural resting states

When you’re learning something new, especially something that’s a bit challenging, your mind needs to be able to go back and forth between the two different learning modes. Study something hard by focusing intently. Then take a break or at least change your focus to something different for a while. During this time of seeming relaxation, your brain’s diffuse mode has a chance to work away in the background and help you out with your conceptual understanding.

Salvador Dali and Thomas Edison are two well-known innovators who leveraged interleaving between these phases. They would hold onto objects while falling asleep in their chairs. They would think of a problem and once they lost consciousness the object they held would fall to the floor and wake them up. Many of their imaginative ideas came from this state.

2/ Memory

Working Memory

- The part of memory that has to do with what you’re immediately and consciously processing in your mind. It is centred out of the prefrontal cortex. There are also connections to other parts of your brain so you can access long-term memories.

- Working memory holds only about four items at a time.

- You often need to keep repeating what you’re trying to work with so it stays in your working memory; for example repeat a phone number to yourself until you have a chance to write it down. You may find yourself shutting your eyes to keep any other items from intruding into the limited slots of your working memory as you concentrate.

Long Term Memory

- Wide storage warehouse distributed over the brain.

- It is immense and has so many items that they can bury each other.

To move information into long-term memory, it often takes time and practice. To help with this process use a technique called Spaced Repetition.

Research has shown that when you first try to put an item of information in long-term memory, you need to revisit it at least a few times to increase the chances that you’ll be able to find it later when you might need it.

You might be surprised to learn that just plain being awake creates toxic products in your brain.

Sleep is your brain’s way of keeping itself healthy. When you sleep, your brain cells shrink. This causes an increase in the space between your brain cells. Fluid can flow past these cells and wash the toxins out.

Sleep is also an important part of the memory and learning process. It seems that during sleep, your brain tidies up ideas and concepts you’re thinking about and learning. It erases the less important parts of memory and simultaneously strengthens areas that you need or want to remember. During sleep, your brain also rehearses some of the tougher parts of whatever you’re trying to learn, going over and over neural patterns to deepen and strengthen them.

Sleep has also been shown to make a remarkable difference in your ability to figure out difficult problems and to understand what you’re trying to learn.

3/ How to improve your memory

- Recall

- Simply looking away and seeing what you can recall from the material you’ve just read is a more productive approach than simply rereading. Using recall, mental retrieval of the key ideas, rather than passive rereading, will make your study time more focused and effective. The only time rereading text seems to be effective, is if you let time pass between the rereading, so that it becomes more of an exercise in spaced repetition.

- Another tip is recalling material when you are outside your usual place of study can also help you strengthen your grasp of the material. You don’t realize it, but when you are learning something new you can often take in subliminal cues for the room and the space around you at the time you were originally learning the material.

- Mnemonics

- Let’s say you want to remember four plants that help ward off vampires; garlic, rose, hawthorn, and mustard. The first letters abbreviate to GRHM. so all you need to do to remember is to use the image of Graham cracker.

- Highlighting and Underlining

- It must be done very carefully. Otherwise it can not only be ineffective, but also misleading. If you do mark up the text, try to look for main ideas before making any marks. And try to keep your underlining or highlighting to a minimum. On the other hand, words or notes in a margin that synthesizes key concepts are a very good idea.

- Visual/Spatial Memory

- Our mind is built for visual/spatial memory. For example, if you were asked to look around a house you never visited before, you’d soon have a sense of the general furniture layout. We can tap into this memory by associating strange and funny images to memorize a concept. We can use spaced repetition to commit this relationship to long term memory. The more senses you use the easier it is to commit to memory.

- Memory Palace Technique

- Is a particularly powerful way of grouping things you want to remember. It involves calling to mind a familiar place like the layout of your house and using it as a visual notepad where you can deposit the concept images that you want to remember. You would imagine yourself walking through a place you know well, coupled with shockingly memorable images of what you want to remember.

Memory tricks allow people to expand their working memory with easy access to long term memory. What’s more, the memory process itself becomes an exercise in creativity. The more you memorize using these innovative techniques, the more creative you become.

4/ Chunking

What is a Chunk?

Chunking is the mental leap that helps you unite bits of information together through meaning. The new logical whole makes the chunk easier to remember, and also makes it easier to fit the chunk into the larger picture of what you’re learning.

Once you chunk an idea, a concept, or an action, you don’t need to remember all the little underlying details. You’ve got the main idea, the chunk, and that’s enough.

How to form a chunk?

The best chunks are the ones that are so well ingrained that you don’t even have to consciously think about connecting the neural patterns together. That actually is the point of making complex ideas, movements or reactions into a single chunk.

- Focus your undivided attention on the information you want to chunk (limited short term memory)

- Understand the basic idea of what you want to chunk.

- It helps hold the underlying memory traces together

- It creates broad encompassing traces that can link to other memory traces

- Practice and repetition with context

- Context means going beyond the initial problem and seeing more broadly

- Helps you see how your new formed chunks fit in the bigger picture

It is as if you have an attention octopus that slips its tentacles through those four slots of working memory when necessary to help you make connections to information that you might have in various parts of your brain.

The value of a Library of Chunks

Basically what people do to enhance their knowledge and gain expertise, is to gradually build the number of chunks in their mind, valuable bits of information they can piece together in new and creative ways.

Chunks can also help you understand new concepts. This is because when you grasp one chunk, you’ll find that that chunk can be related in surprising ways to similar chunks, not only in that field but also in very different fields. This idea is called transfer.

If you have a library of concepts and solutions internalized as chunked patterns, you can think of it as a collection or a library of neural patterns. When you’re trying to figure something out, if you have a good library of these chunks, you can more easily skip to the right solution by, metaphorically speaking, listening to whispers from your diffuse mode. Your diffuse mode can help you connect two or more chunks together in new ways to solve novel problems. Another way to think of it is this, as you build each chunk it is filling in a part of your larger knowledge picture, but if you don’t practice with your growing chunks, they can remain faint and it’s harder to put together the big picture of what you’re trying to learn.

There are two ways to figure something out or to solve problems. First, through sequential step-by-step reasoning and second, through a more holistic intuition. Sequential thinking where each small step leads deliberately towards a solution, involves the focused mode. Intuition on the other hand often seems to require this creative diffuse mode linking of several seemingly different focused mode thoughts. Most difficult problems and concepts are grasped through intuition, because these new ideas make a leap away from what you’re familiar with. Keep in mind that the diffuse modes, semi-random way of making connections means that the solutions it provides should be very carefully verified using the focused mode. Intuitive insights aren’t always correct.

Interleaving

Mastering a new subject means learning not only the basic chunks, but also learning how to select and use different chunks. The best way to learn is by practicing jumping back and forth between problems or situations that require different techniques or strategies. Interleaving is extraordinarily important. Although practice and repetition is important in helping build solid neural patterns to draw on, it’s interleaving that starts building flexibility and creativity.

5/ Procrastination

Procrastination is the act of unnecessarily and voluntarily delaying or postponing something despite knowing that there will be negative consequences for doing so.

Procrastination is an easy habit to develop because of the reward. It shares features with addiction. It offers temporary excitement and relief from sometimes boring reality.

What is a habit?

Habit is an energy saver for us. It allows us to free our mind for other types of activities. You go into this habitual zombie far more often than you might think, that’s the point of habit. You don’t have to think in a focused manner about what you are doing while you are performing the habit, it saves energy. Habits can be good and bad, they can be brief like absently brushing back your hair or they can be long for example when you take a walk or watch television for a few hours after you get home from work.

You can think of habits as having 4 parts:

- The cue: this is the trigger that launches you into zombie mode

- The routine: what we do in reaction to that cue. This is your zombie mode. Zombie responses can be useful, harmless or sometimes harmful.

- The reward: every habit develops and continues because it rewards us. It gives us an immediate little feeling of pleasure.

- The belief: habits have power because your belief in them. To change a habit you need to change your underlying belief.

If you find yourself avoiding certain tasks because they make you feel uncomfortable, you should know there’s another helpful way to re-frame things and that’s to learn to focus on process not product. Process means the flow of time and the habits and actions associated with that flow of time. As in, I’m going to spend 20 minutes working. Product is an outcome, for example, a homework assignment that you need to finish. To prevent procrastination you want to avoid concentrating on the product. Instead your attention should be on building processes. The essential idea here is that the zombie habitual part of your brain likes processes because it can march mindlessly along.

Harnessing your zombies

The trick to overriding a habit is to look to change your reaction to a cue. The only place you need to apply will power is to change your reaction to the cue. To understand that, it helps to go back through the four components of habit and we analyze them from the perspective of procrastination:

- Cue

- It usually falls into one of the following categories: location, time, how you feel and reactions, either to other people or to something that just happened. Do you look something up on the web and then find yourself web surfing? The issue with procrastination is that, because it’s an automatic habit, you’re often unaware that you’ve begun to procrastinate. You can prevent the most damaging cues by shutting off your cell phone or keeping away from the internet and other distractions for brief periods of time, as when you’re doing a pomodoro.

- Routine

- The key to rewiring is to have a plan. Developing a new ritual can be helpful. Some students make it a habit to leave their phone in their car when they head for class which removes a potent distraction.

- The reward

- It helps to add a new reward if you want to overcome your previous cravings. Only once your brain starts expecting that reward, will the important rewiring take place that will allow you to create new habits.

- The belief

- The most important part of changing your procrastination habit is the belief that you can do it.

6/ Juggling Life and Learning

A good way for you to keep perspective about what you’re trying to learn and accomplish is to once a week write a brief weekly list of key tasks in a planner journal. Then each day on another page of your planner, write a list of the tasks that you can reasonably work on or accomplish (The list should be short, 6 items for example where some are process oriented and others product oriented). Try to write this daily task list the evening before. Why? Research has shown that this helps your subconscious to grapple with the tasks on the list, so you can figure out how to accomplish them. Writing the list before you go to sleep enlists your zombies to help you accomplish the items on the list the next day. If you don’t write your tasks down on a list, they lurk at the edge of the four or so slots in your working memory, taking up valuable mental real estate. But once you make a task list, it frees working memory for problem-solving.

Thanks for reading, I hope you enjoyed it!